HOW TO TRAVEL BETTER

Protecting the Burren’s Identity

Ireland’s west coast has inspired writers, poets and travelers for centuries. Today, locals sustain the fragile landscape’s legacy.

Vic O’Sullivan

understanding the burren

And some time make the time to drive out west

Into County Clare, along the Flaggy Shore,

In September or October, when the wind

And the light are working off each other

So that the ocean on one side is wild

With foam and glitter, and inland among stones

The surface of a slate-grey lake is lit…

Irish Poet Seamus Heaney,

excerpt from “Postscript”

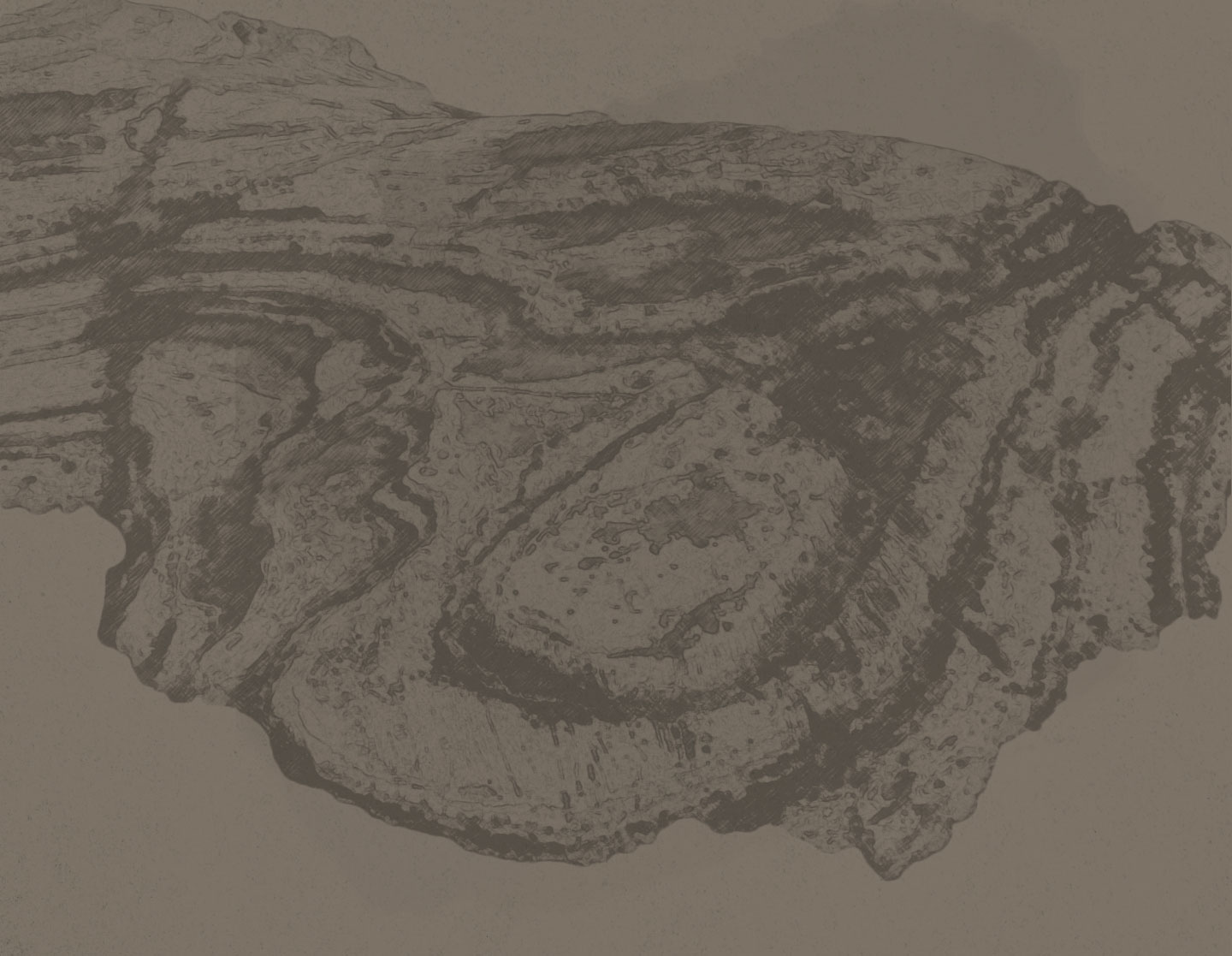

Spanning the northwest territory of County Clare in a gradual evolution of contrasting colors, Ireland’s Burren and Cliffs of Moher UNESCO Global Geopark is fringed by lush green lake lands to the east that lead to vast plains of smooth silver limestone before reaching its westerly shores, where land ends, plunging into the ivory-capped waves of the Atlantic Ocean.

The

Burren

CLICK ON POINTS TO EXPLORE

UNDERSTANDING

THE BURREN

This magnificent and unique frontier of Western Europe has gained global recognition for its astonishing beauty, but that comes with a price tag — overtourism — or specifically, the inevitable scarring of the park’s fragile ecosystem by thoughtless practices.

However, it’s not the first time the Burren’s fragile landscape has been put at risk by human exploration. Beneath the geopark, which has one of the largest karst surfaces in Europe, lies a labyrinth of largely unexplored caves, passages, and rivers that reveals the lifestyle of prehistoric humans.

While there is evidence of hunter-gatherers in Ireland dating back 33,000 years, farming tools, human bones and livestock remains discovered beneath the Burren’s cavernous underworld indicate that Neolithic Human was the first culprit in the large-scale destruction leveled on the landscape some 6,000 years ago.

It wasn’t until the early Middle Ages that we can see proof of how the local community set the template for environmentally friendly farming practices — a legacy that still lingers today with a network of tourism businesses working hard to sustain the Burren’s natural resources and beauty.

the people

THE PEOPLE –

PAST & PRESENT

The millennia of aggressive farming, known as “agri-vandalism,” along with glacial movements and erosion, obliterated forests and turned the soil barren, leaving the Burren’s austere splendor in its wake.

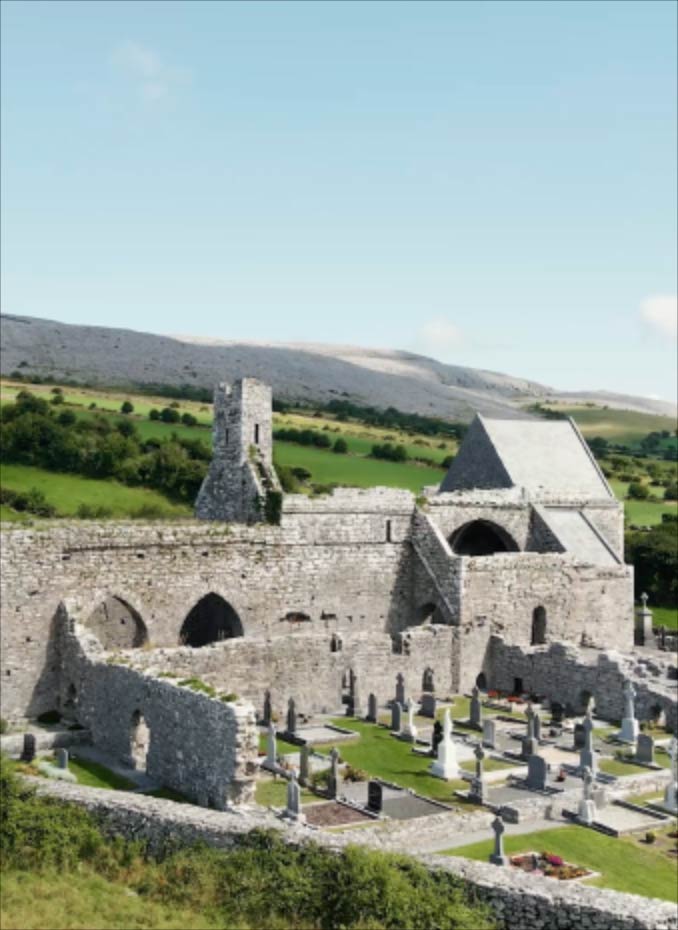

It was only once the land lay desolate that farmers, including 12th-century monks at Corcomroe Abbey in the park’s northwest corner, learned to work in harmony with the rocky terrain.

While the dramatic and enduring appeal of the park is no longer at risk of damage from agri-vandalism, the relatively new phenomenon of over tourism is leaving its mark — but this time, the community is out in force to safeguard the Burren’s fragile environment by placing sustainable practices at the fore.

Jarlath O’Dwyer, head of the Burren Ecotourism Network— a syndicate of local businesses in the tourism sector, from restaurants to major landmarks —explains the network’s commitment to sustainable tourism.

“It’s a platform which enables all member businesses to commit to a code of standard measures which collects and collates data around their energy consumption, waste output and water usage.”

Jarlath O’Dwyer

In a nutshell, tourism members commit to undertake essential tasks that contribute to the area’s conservation by protecting the ocean waters, guarding the Burren’s landscape from harm and putting in place sustainable farming practices to nourish the local soil.

The Ocean

THE OCEAN

While the otherworldly beauty of the Burren — with its bare, wind-whipped mountains, twisting caves and 5,000-year-old Poulnabrone Dolmen burial portal — is a magnet for visitors, the area’s undeniable star attraction is the magnificent, colossal Cliffs of Moher.

Rising 700 feet over the ocean and stretching for miles along the County Clare coastline, the cliffs are the ultimate Instagram backdrop and generally lure almost 2 million visitors annually, making them the second-most visited attraction in Ireland (after the Guinness Storehouse in Dublin).

With that volume of traffic, predictably, responsible tourism is a pivotal factor when it comes to showcasing the cliffs to visitors.

Mark O’Shaughnessy, head of operations at the Cliffs of Moher Visitor Site, says that his operation works within a sustainable environment that protects natural resources while remaining financially viable and giving back to the local community.

He also stresses that the Cliffs of Moher site uses indigenous design and products, including, “the natural materials and forms of the area to minimize its impact visually on the rural landscape setting, such as the subterranean visitor center, which is built into the hillside, and the use of local Liscannor flagstone along the cliffs’ paths.”

An on-site “Green Team” ensures that the visitor center leaves a small ecological footprint by employing the latest green technology in LED lighting and low CO2 emissions, as well as an air-to-water system and geothermal ground pump to heat and cool the main visitor center building. However, the staff is equally concerned about the greater environment well beyond the cliffs, according to O’Shaughnessy.

“We also promote sustainable travel by encouraging public transport, walking and cycling to the cliffs,” he says.

“We preserve and monitor the natural habitat of the Cliffs of Moher and work closely with the local tourism community to ensure the future sustainability of the area.”

Mark O’Shaughnessy

One such member of this community is the Doolin Ferry Company. It’s one of two Doolin Village–based operators who offer cruises beneath the Cliffs of Moher and a shuttle service to the nearby Aran Islands.

The tiny Aran archipelago appeared in the ocean 10,000 years ago, when waters rose during a period of sustained global warming, separating the islands’ landscape from the mainland and Burren Park.

Edel Vaughan, director of sales for Doolin Ferry Company, says that her company has worked hard to protect the coastline’s limestone pavements and sandy beaches, along with ocean life, since it started operations more than 50 years ago.

In addition to offering ticketless fares, using low-emission aluminum vessels and ensuring responsible waste and sewage treatment, in 2020 the company marked another major step forward in sustainable tourism: They introduced a new express ferry to their fleet, the Aran Islands Express.

The new vessel increases the capacity of a single ferry from 100 passengers to 250. “This allows us to conserve fuel usage by not operating several smaller boats at the same time,” says Vaughan. “We have greatly improved the efficiency of our service to work toward meeting our sustainability and environmental goals.”

By working in tandem with the Burren Network and recruiting crew members from the local area who share their respect for the park’s heritage and landscape with visitors, the Doolin Ferry Company offers more than scenery.

“Our staff and crew are trained in the geology and ecology of the landscapes in which we operate.

We have trained our crew and staff to then share this knowledge with our on-board commentaries.”

EDEL VAUGHAN

It’s this knowledge that remains with visitors once they return to land, to the starkly beautiful Burren landscape. Doolin’s passengers gain an understanding of place — and become part of that sustainable tourism network.

the landscape

ON THE BURREN

LANDSCAPE

This is the time to be slow,

Lie low to the wall

Until the bitter weather passes.

Irish Poet and Author John O’Donohue,

excerpt from “This Is the Time to be Slow”

Before the establishment of the Burren Ecotourism Network, writers, poets and film crews explored the craggy local landscape to capture the brutal beauty of northwest Clare in their work.

The Cliffs of Moher has featured in movies like “The Princess Bride” (1987) and “Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince” (2009), while writers such as C.S. Lewis (“The Chronicles of Narnia”) and J.R.R. Tolkien (“The Lord of the Rings”) were regular visitors who drew inspiration from the geopark’s end-of-world magnificence.

However, it was poet, author and philosopher John O’Donohue who made the Burren his home and muse, offering early morning spiritual retreats at Corcomroe Abbey and campaigning against development at the perfectly formed Mullaghmore, a smooth limestone mountain.

Heart of Burren

HEART OF

THE BURREN

O’Donohue’s love for the land is carried on by people such as walking guide Tony Kirby, who owns Heart of the Burren Walks. He explains that the geopark’s unique landscape and wildlife provide an enduring draw for visitors.

“Whereas all the rest of the other uplands of the Atlantic fringe of Ireland are defined by the iconic Irish landscape of bog, the Burren is home to a most idiosyncratic land form, limestone pavement, where in springtime the drab gray uplands are transformed into a mesmerizing mélange of wild plants with origins in different parts of the world. The Burren in Bloom is one of Europe’s great annual natural history events.”

When it comes to sustainable travel, Kirby is reminded of St. Colman’s Hermitage, a rich complex of monuments at the base of a 350-foot sheer cliff in a woodland setting that he describes as a “Celtic rainforest.”

It’s a place where time stands still — and that, according to Kirby, is the key to sustainable tourism.

“I see it here in the Burren, where the social, environmental and economic effect of ‘fast tourism’ is significant,” he says. “Our challenge is to attract a slower tourist. He and she will spend more time in the region, support the local economy, interact with community and depart having had a very rich visitor experience.”

the soil

FROM THE SOIL

If you remain generous,

Time will come good;

And you will find your feet

Again on fresh pastures of promise,

Where the air will be kind

And blushed with beginning.

Irish Poet and Author John O’Donhue,

excerpt from “This Is the Time to be Slow”

When it comes to food tourism, Burren Ecotourism Network members prefer to take things slowly, nurturing the land and offering visitors the opportunity to sample their produce in local restaurants or at events like the Burren Slow Food Festival or Burren Food Fayre.

Aidan McGrath, chef and owner of MICHELIN-Starred restaurant Wild Honey Inn in Lisdoonvarna, says that as his business evolves ecologically with an eye on the future, he currently ensures they use “like-minded suppliers of wild and organic produce and electricity generated from wind farms and biogas for our heating and cooking, which helps reduce our carbon footprint.”

Similarly, Birgitta Curtin (a founding member of the Burren Ecotourism Network), who, along with husband Peter, owns the Burren Smokehouse, the Roadside Tavern and the Burren Brewery, believes that using the old traditional methods of food production allows her to work organically with the land and mitigate her ecological footprint.

To that end, Siobhán Ní Gháirbhith, owner of St Tola Irish Goat Cheese on the southern rim of the Burren, recognizes that goats have shared the landscape with man for millennia.

“We do not force the land or our goats but protect it by working with Mother Nature for the sustainable long-term benefit for all those creatures that live on it and live of it, including those who visit this beautiful unique area.”

Siobhán Ní Gháirbhith

Taste of Burren

Taste of Burren

Lisdoonvarna

One of the oldest gastropubs and microbrewery in the Burren area, the Roadside Tavern has been passed down through the Curtin family since 1893. Proprietor Peter Curtin invites visitors to settle in for live music or sample one of the crafted beers brewed in house.

Lisdoonvarna

Founded by Birgitta Curtin in 1989, Burren Smokehouse is a producer of smoked fish – salmon, mackerel, trout, and eel – in the Lisdoonvarna area

Lisdoonvarna

Nestled in the Burren National Park, this country inn boasts Ireland’s only MICHELIN Starred pub.

Gorbofearna

Owned and operated by Siobhan Ni Ghairbhith since 1999, St. Tola handmakes 11 varietals ranging from fresh, soft cheese to Gouda style hard cheese.

the future

LOOKING TOWARDS

THE FUTURE

Despite the community’s best efforts, the region’s staggering beauty has led to the inevitable signs of overtourism, culminating in pollution or vandalism — such as people shattering limestone pavements into fragments and reassembling the pieces to create fake “mini-dolmens” (replicas of the Burren’s most famous portal tomb).

Day bus tours from the major cities often leave little economic return for the community, only reminders of their visits by choking traffic on country lanes or waste in the form of cigarette butts or garbage discarded at scenic “pit stops.” Similarly, the scorched scars of campfires in unauthorized zones blight the landscape.

Dr. Brendan Dunford, a founding member of Burrenbeo Trust, a charity dedicated to protecting the landscape, is concerned about the increase in footfall and the problems it creates for the Burren.

“In spite of appearances, it’s a fragile landscape,” he says. “Damage to delicate habitats, archaeological sites or geological features can easily occur, and it’s infuriating to see people pick rare flowers, build ‘mini dolmens’ or wantonly smash blocks of waterworn limestone.”

He adds that few visitors seem to realize that most of the Burren is privately owned farmland. He says that handcrafted drystone walls are often damaged, while “parking in front of farm gates or stalking livestock for a selfie may be causing big problems for farmers and their stock.”

However, Dunford remains optimistic about the future.

“The heritage of the Burren — from flowers to dolmens, limestone pavements to feral goats — has been shaped by 6,000 years of farming activity.”

Dr. Brendan Dunford

“The heritage of the Burren — from flowers to dolmens, limestone pavements to feral goats — has been shaped by 6,000 years of farming activity,” he says.” Hopefully, tourism can help support farm families economically so that they can continue to look after the landscape that attracts these tourists in the first place. We also need to invest in local communities as the future guardians of the landscape.”

With the area representing a major stopping point along Ireland’s 1,600-mile Wild Atlantic Way driving route, the nation’s Minister for Tourism, Catherine Martin, agrees.

“Our natural assets, such as the Burren and the Cliffs of Moher, are a major contributing factor to Ireland’s overall attractiveness as a tourism destination,” she says. “The focus for sustainable tourism must strike a balance between the economic benefits and the need to protect these invaluable natural assets and preserve them for future generations.”