HOW TO TRAVEL BETTER

Pride

Lives

Here

Sustaining New York City’s LGBTQ+ Spaces

DIANA HUBBELL

Pride Lives Here

From Stonewall in 1969 to the ballroom scene of the 1980s, New York City has a powerful history and symbolic weight for the global LGBTQ+ community.

While inclusivity has been central to the city’s identity for decades, many of its queer-friendly spaces have been especially vulnerable to the economic hardships of COVID-19.

From drag bars to nightclubs, these venues rely on the support of New Yorkers and the 67 million annual tourists who visited the city prior to the pandemic. Therapy, a gay club; Meme’s Diner, a self-declared “radically queer” space; The Pyramid Club, a drag performance venue; and China Chalet, home to countless LGBTQ+ parties, all shuttered during the last year.

As New York reopened to travelers and the city launched a $30 million NYC Reawakens tourism campaign, LGBTQ+ activists continued rallying to save this critical element of New York’s culture.

Visitors seeking to travel better during their stay in the city can help by putting their dollars where they’re needed and by engaging deeply with the history that makes these safe spaces so important.

SAFE HAVENS

Protecting Safe

Havens

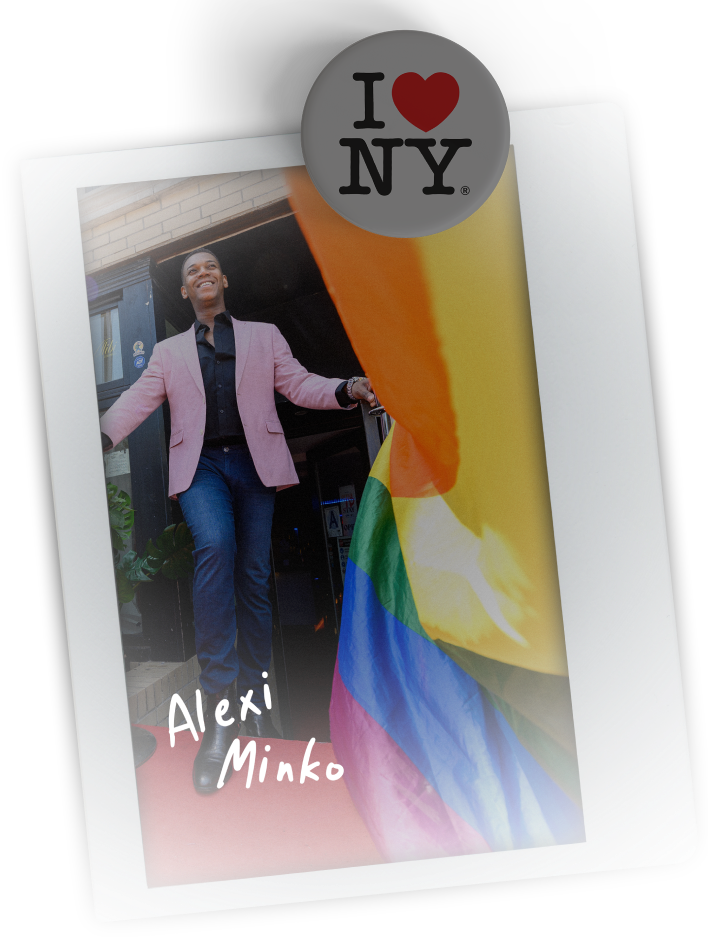

Alibi Lounge, Harlem

On June 24, 2021, Alibi, one of New York’s only Black-owned LGBTQ+ bars, celebrated its five-year anniversary in Harlem.

Owner Alexi Minko says it will be a remarkable moment, in part because it’s not one that he expected to see.

In March 2021, Minko was physically assaulted and robbed in his own bar. While he was still healing from his injuries, the city of New York ordered restaurants and bars to close to slow the spread of COVID-19. With bills piling up, he found himself questioning if he wanted to go on with the business at all.

“I had to recover physically and mentally first,” he says. Minko, who originally hails from Gabon, even contemplated saying goodbye to the city he has loved and called home for more than 15 years. “I wasn’t sure I wanted to continue with the lounge. I already had the paperwork to release the space.”

“You can’t let people in

your own community

down. People come to

Alibi because they feel

safe, they feel welcome,

they feel understood.”

ALEXI MINKO

A friend reached out to him in that dark moment and suggested he start a GoFundMe. Minko initially balked at the idea but decided to put up a request for a modest $6,000 to help pay his staff. The campaign went viral, with donations pouring in not just from fellow New Yorkers, but from former travelers who had stopped by the bar or who dreamed of one day doing so. By the time Minko closed the campaign, it had raised more than $183,000.

“It was insane to see people from all over the world who had never met me but who believed that the only gay-owned bar in Harlem had to stay open,” Minko says. “It put a certain responsibility on me. You can’t let people in your own community down. People come to Alibi because they feel safe, they feel welcome, they feel understood. If we were to close, where would they go? And with the closing of LGBTQ+ spaces all over the country, who is to say that another space like Alibi would open?”

Alibi’s story has a happy ending — Minko recently signed a new lease, and the bar’s future is secure for the time being — but it underscores the precarious state of LGBTQ+ bars.

From the Stonewall Inn to Julius’ Bar, bars have been central to the history of New York’s queer liberation movement. And Minko, who has a background in international human rights law, has a deep appreciation for the role that Alibi plays.

“We are a safe haven for people in our community, for transgender youth who might be harassed elsewhere,” Minko says. “That’s the importance of supporting LGBTQ+ spaces around the world.”

To be sure, visitors to New York City can still make a difference for these spaces. Julius’ Bar in Greenwich Village, which was the site of a 1966 “sip-in” protest by the Mattachine Society, an early advocacy society for LGBTQ+ rights, was able to survive the pandemic thanks to more than $116,000 in donations, in addition to funding from the Gill Foundation.

Nevertheless, owner Helen Buford says more visitors need to spread the word so that Julius’ Bar and others like it can continue to serve the community.

“To people who are traveling: Plan your itinerary to try to support as many LGBTQ+ spaces as you can,” Buford says. “We all want to survive.”

DRAG & ACTIVISM

Honoring the History of Drag and Activism

West Village

To some, it might seem like Marti Allen-Cummings — who announced their candidacy for City Council in 2019 — found an unusual path to politics.

Just as generations of LGBTQ+ folk have done, Allen-Cummings initially traveled to New York shortly after graduating from high school because of its thriving queer culture and prevalence of safe, inclusive spaces.

After moving to the city, they were drawn to the city’s drag performance scene, where they remain an active performer to this day. Even now, Allen-Cummings has continued to perform on stage despite a demanding campaign schedule.

“There’s no right or

wrong way to do drag.

Everyone’s drag is

uniquely theirs. ”

MARTI ALLEN-CUMMING

“Drag in and of itself is an act of political resistance,” Allen-Cummings says. “There’s no right or wrong way to do drag. Everyone’s drag is uniquely theirs. You get to define the art form for yourself, but in any form, it is going against the patriarchal norms.”

For decades, members of the LGBTQ+ community and allies have traveled to New York in part to honor the city’s history of both drag and queer activism. Long before RuPaul sashayed into television stardom, the city boasted a thriving underground drag scene.

The first balls in New York date back to the Roaring ’20s, but in the wake of Stonewall, the queer ballroom scene exploded. By the 1980s, the ballroom culture depicted in “Paris Is Burning” and “Pose” was a force to be reckoned with and a reason members of the LGBTQ+ community traveled here from all over the world.

Christopher Park in West Village

“Drag artists have marched alongside for much of the queer liberation movement, whether it was at Stonewall, in the fight for marriage equality, in the fight for police accountability, or standing up for Black and Indigenous lives,” Allen-Cummings says.

Allen-Cummings also views drag as a tool for grassroots organizing. From William Dorsey Swann, a former slave and queer liberation icon who hosted secret drag balls in Washington, D.C., in the 1880s, to José Julio Sarria, who became the first openly gay candidate to run for public office in 1961, and Stormé DeLarverie, a drag king and civil rights activist who is said to have thrown the first punch at Stonewall, drag performers have a long, proud history of activism in the United States.

“[Drag’s] a fun, campy art form, but the root of it is grounded in political action.”

MARTI ALLEN-CUMMING

While some of the original ballroom venues from the ’80s may have shuttered, drag queens and kings in New York have kept the culture and traditions alive. Like other live performers, however, drag artists have suffered financially under the pandemic and need support more than ever.

While Allen-Cummings believes fundamental policy changes are necessary to protect workers, they say individual travelers can make a positive impact by showing up and spreading the word. As most drag performers depend on tips, audience support is often the difference between making rent and not.

“If you’re traveling and financially able, go to local queer spaces,” Allen-Cummings says. “Go see local drag artists and musicians and comedians and dancers. Tip them well. Write positive reviews online and share about your experience so that people see them and support them.”

BURLESQUE

Come to the Cabaret

House of Yes, Bushwick

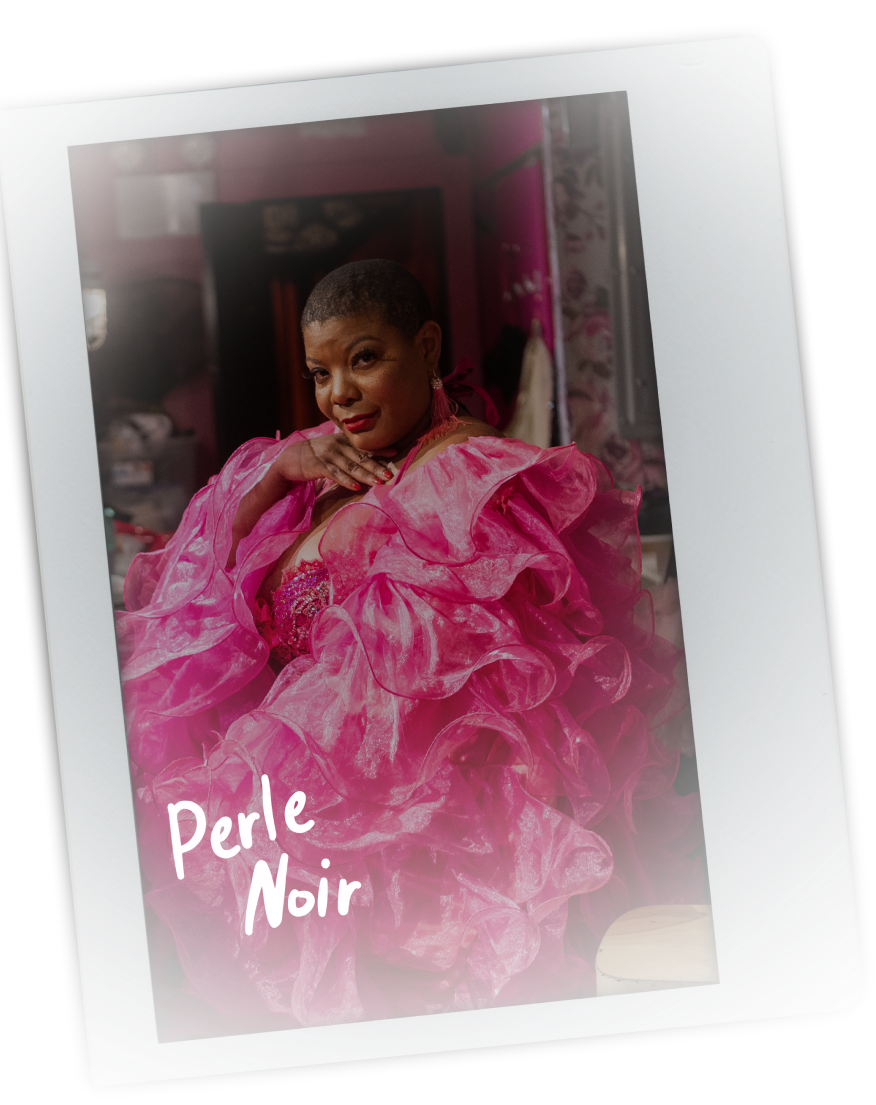

In March 2020, performers clad in rhinestones, feathers and bejeweled nipple pasties twirled across the stage of House of Yes, a queer-friendly nightclub in Bushwick, for The Noire Pageant

The atmosphere was electric — no one knew yet that the club would close for the foreseeable future within a matter of days. At the time, everyone was busy celebrating dancers like Moscato Extatique, a nonbinary performer crowned Duchess of Burlesque, and Crocodile Lightning, a Noire Pageant Queen Ambassador who says the pageant gave her the confidence to come out as a trans woman.

House of Yes in Bushwick

“I am very proud that one of the things I got to do before we shut down was to make history by presenting the only burlesque competition that exists strictly to elevate BIPOC performers,” says Perle Noire, the pageant’s founder and a titan of the New York burlesque scene for more than 15 years. “I want people of color in burlesque to understand that glamour belongs to us as well and that it is up to us to preserve our legacy.”

For Perle Noire, the pageant was the culmination of a decadelong dream. After discovering burlesque in New Orleans, Perle Noire became convinced of the medium’s power as a therapeutic tool and of the need to create a more diverse, inclusive burlesque space. She fled to New York hours before Hurricane Katrina flooded her home in the 9th Ward and has been working to foster that community here ever since.

“I always start [my performances] with a moment of resilience. All of my acts have been inspired by something I have had to overcome,” Perle Noire says.

Although The Noire Pageant will only return live when it is safe to do so without social distancing, Perle Noire has been especially busy during the last year. Many of the performers with whom she collaborates struggled personally and professionally.

“You need to cut open

your heart for the

audience. That means

you have to go in with

your entire story, not just

a chapter.”

PERLE NOIRE

Travelers have been coming to New York to see cabaret shows since the 1800s, but in recent years, performers have been redefining what the medium means. Burlesque remains, as Perle Noire says, the “embodiment of pure glamour and pure beauty.”

Today’s performers are reclaiming that mantle. Troupes like Honey Burlesque, which performs in both New York and Los Angeles, cater specifically to queer women and nonbinary folk, ignoring the male gaze altogether.

Meanwhile, at queer-friendly venues like Pink Metal, The Slipper Room and Club Cumming, neo-burlesque performers often challenge or subvert gender norms. Olive TuPartie, a burlesque dancer and emcee, is thrilled to be dishing up her signature blend of vintage-inspired slapstick comedy, acrobatics and dance at all of these spaces after a long pandemic.

“Drag and burlesque

are basically sisters…

Both of these art

forms poke fun at

the expectations of

gender and sexuality.”

OLIVE TUPARTIE

“If you look at the history of performance art, especially in vaudeville and circus acts, drag and burlesque are basically sisters. They’re two sides of the same coin,” says Olive TuPartie. “Both of these art forms poke fun at the expectations of gender and sexuality.

When COVID-19 struck, Olive TuPartie lost her primary sources of income almost overnight. Unwilling to throw in her tassels, she launched Haus of Olive, a twice-weekly collaborative Zoom variety show with both drag queens and burlesque performers.

Now she and her fellow performers are thrilled to be back in front of live audiences. She is especially proud to show travelers what New York’s distinctive spin on burlesque is. Her hope is that all visitors feel welcome to come to the cabaret and that they travel better by showing the performers their support.

“If you’re traveling to this city, purchase tickets early and tip your performers generously. I always carry a big bag of one-dollar bills whenever I go anywhere,” Olive TuPartie says. “And be sure to warm up your vocal cords to be as loud as humanly possible because we’ve all been in quarantine for a year and it means the world to us.”

LESBIAN BARS

Saving New York City’s Last Lesbian Bar

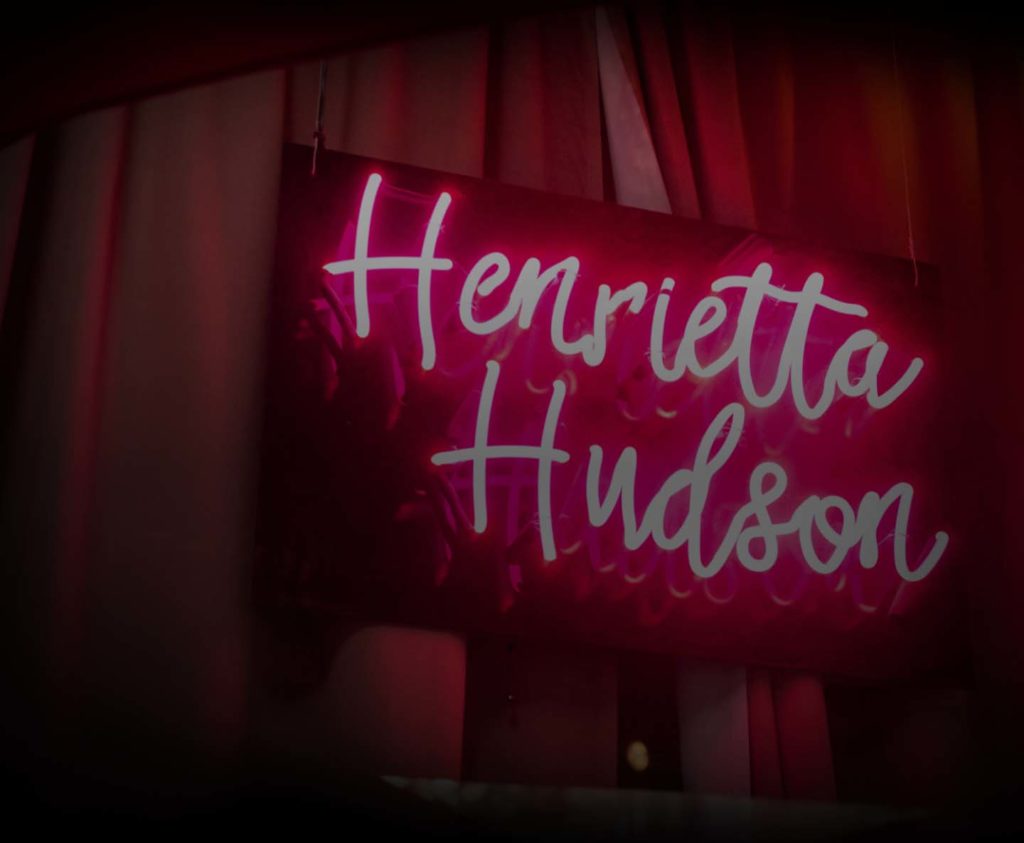

Henrietta Hudson, West Village

Lesbian bars around the United States were already in trouble long before the pandemic struck.

By some estimates, there were more than 200 of them in the 1980s — a number that had plummeted to just 15 by 2019. Many large cities with thriving LGBTQ+ communities, including Los Angeles, no longer have a single bar that caters to queer women. For activists, the decline is alarming, and calls from the Lesbian Bar Project and other organizations have been rising to protect these spaces.

New York has three such spaces remaining, one of which, Ginger’s, has yet to reopen since the onset of COVID-19. Cubbyhole, founded in 1983, reopened in the West Village, as did nearby Henrietta Hudson, founded in 1991.

All of these bars have been de facto community hubs for queer women from around the world for years, in part because so few are left anywhere, LGBTQ+ travelers often make a point of stopping by.

While most bars in New York are more welcoming toward LGBTQ+ patrons these days, Lisa Cannistraci, owner of Henrietta Hudson, says these places still serve a vital need, particularly when times are tough.

“You don’t know when political climates are going to change, so we can’t lose these spaces,” Cannistraci says. The day after the 2016 election, the line for her bar wound all the way down the street.

While the surge of customers was largely due to concern about the future of LGBTQ+ rights under the incoming administration, it was also indicative of the new direction Henrietta Hudson had recently undertaken.

“Inclusivity is not

choice for me; it’s

a reflex.”

LISA CANNISTRACI

“People have to remember that Stonewall was spearheaded by a trans woman of color, Marsha P. Johnson, and a Black butch lesbian, Stormé DeLarverie. The first Pride, they were excluded. Anyone who identifies as a lesbian and isn’t inclusive needs to look at our history,” Cannistraci says.

So far, business at both Henrietta Hudson and Cubbyhole has been booming; however, more support is needed. More than anything, Cannistraci wants to provide a welcoming place for LGBTQ+ folks from all over.

Since the limited space at her bar tends to book up, she hopes that visitors will reserve early and stop by to raise a glass. “As far as travelers go, come by,” Cannistraci says. “Henrietta’s is back, and it’s beautiful.”

If You Go