HOW TO TRAVEL BETTER

Reef Resilience

On Australia’s Great Barrier Reef,

tourism inspires conservation

Nina Karnikowski

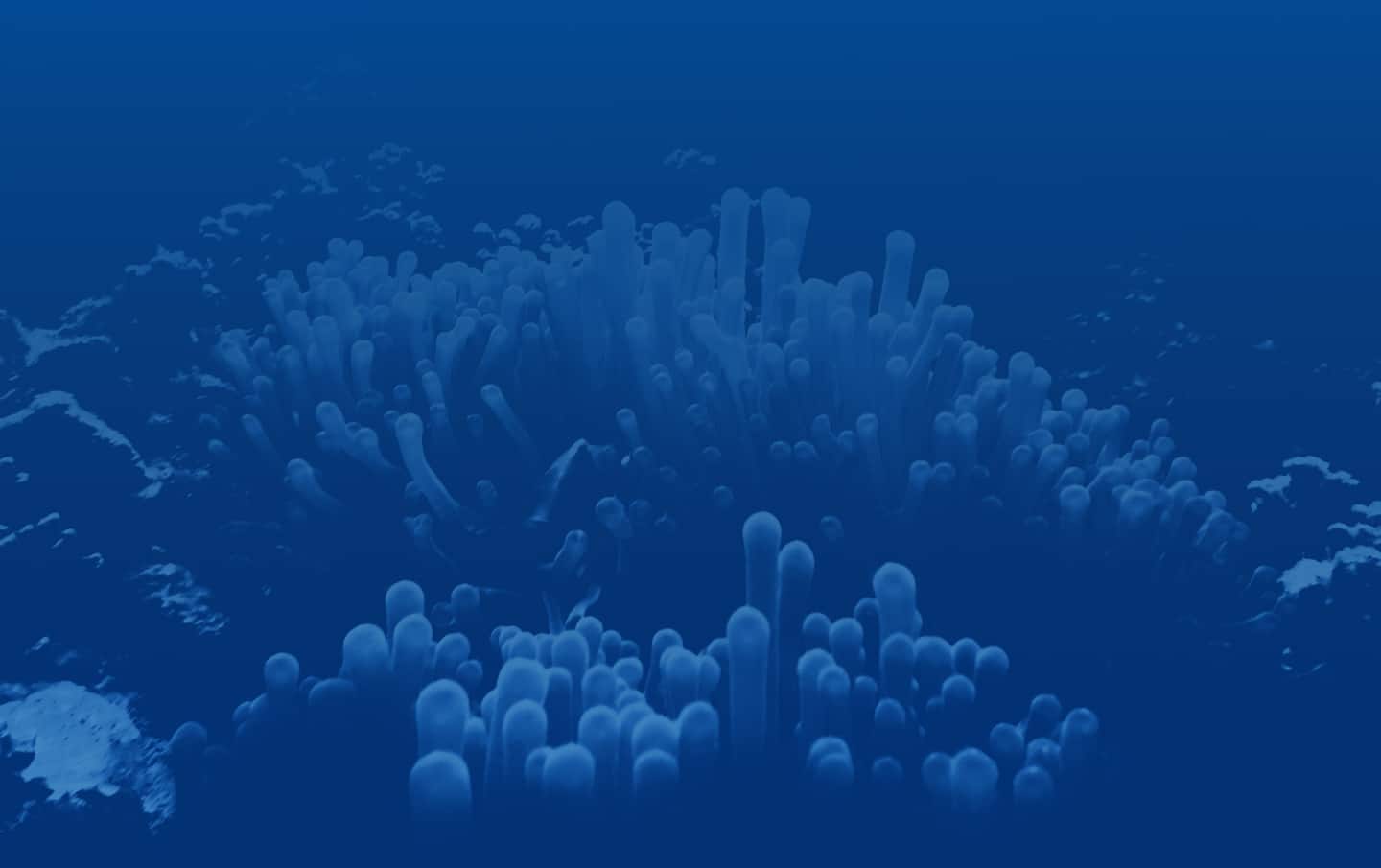

Tumbling off the back of a dive boat on many sections of Queensland, Australia’s, Great Barrier Reef, a traveler will be greeted by technicolor coral beds filled with glittering tropical fish as large as dinner platters, turtles and reef sharks drifting through aquamarine waters, magnetic blue starfish, and Christmas tree worms fringed in bright yellow, orange and purple twisting out of their coral homes.

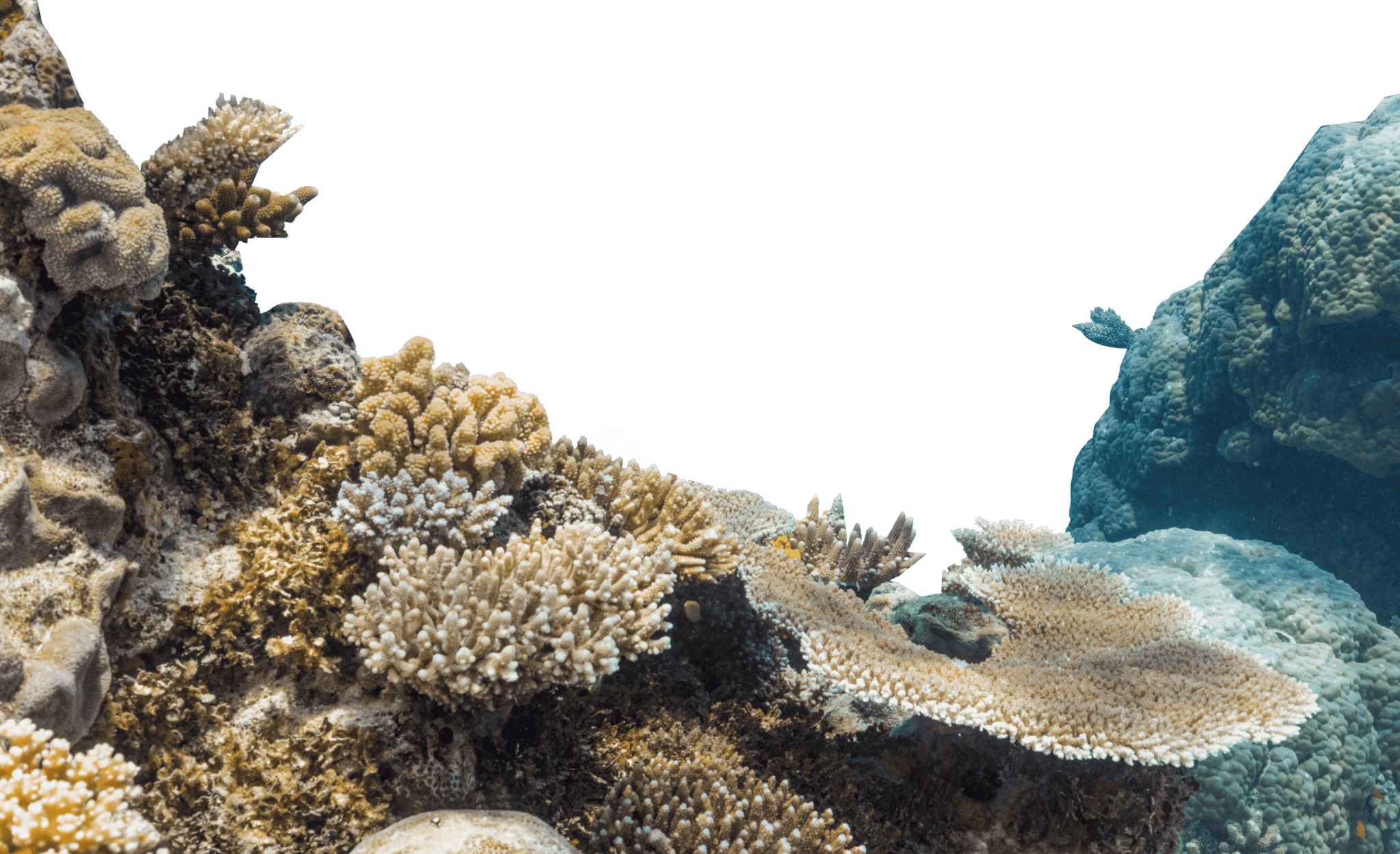

Precisely because of this extraordinary natural beauty and the reef’s UNESCO World Heritage status, it has become a global emblem for the impact of climate change on biodiversity. The countless challenges the reef faces have been widely documented: three mass coral bleaching events in five years, cyclonic storms, increased coastal development, crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks, declining fish populations due to rising sea temperatures, and more. To date, as much as 50 percent of the reef’s coral cover has now been lost.

But while the threats this 1,430-mile (2,300-kilometer) stretch of intersecting reefs faces are very real and urgent, local environmental and tourism experts say that reminding tourists of the staggering diversity of marine life still left to see there is of utmost importance since tourists are one of the most vital parts of the reef’s life-support system.

Great Barrier Reef

SUSTAINING

THE REEF

The biological importance of the Great Barrier Reef has been clear for decades. Home to upward of 1,600 species of fish and one-third of the world’s soft coral, UNESCO designated it a World Heritage site in 1981. Then, in 2018, researchers proved it to be of immense economic value, as well.

A landmark study by Deloitte Access Economics valued the reef at $56 billion, with more than half that sum — $29 billion, to be exact — generated by tourism. The numbers clearly show how valuable travelers and their dollars really are to the reef.

“Tourism is one of the only ways the Australian government values the Great Barrier Reef’s longevity,” says Dean Miller, managing director of the nonprofit Great Barrier Reef Legacy.

“So what the reef needs is support in terms of tourism and visitation. We need to let the world know that while it is doing it tough, it’s still in very good condition, in fact, probably the best condition of any reef system on the planet.”

DEAN MILLER

Conservation

TRAVEL INSPIRING CONSERVATION

In 2019, Great Barrier Reef Legacy co-created the world’s first Living Coral Biobank, which Miller has described as an “insurance policy” for the world’s coral reefs. The Biobank’s master plan is to collect and house all 800 of the world’s fast-disappearing hard coral species in a holding facility in Port Douglas, with the hope they could help restore damaged reefs in the future.

Because the project receives no government funding and survives entirely on public donations and tourism dollars, Great Barrier Reef Legacy co-runs citizen-science-themed trips where tourists can observe Biobank coral collections take place.

“Trips like this are valuable in three ways,” explains Miller. “Our partners Australian Geographic and Coral Expeditions donated $30,000 to the Biobank from the last trip, so we were able to get some important funding while we went out to do the work we needed to do, plus we got to share that with the Australian public on board.”

This symbiotic relationship forged between tourism operators, scientists and tourists offers a practical solution to maintaining the reef’s health. The other benefit of this intersection, according to Miller, is that each tourist who visits the reef can then become an ambassador for it.

“Pre-COVID there were something like two million visitors accessing the reef each year; they should be two million ambassadors who walk away saying ‘I’m going to do something.This is way too special to let slip,” he says.

That might be making donations to a nonprofit like ours or going home and changing their behavior, but that’s what traveling here inspires in people.”

DEAN MILLER

Still, the paradox is that one of the major causes of reef degradation — rising sea temperatures due to global warming — is increased by the emissions-heavy activities inherent in tourism, including travel by plane and gas-powered boats.

Citizen Scientists

SCALING

CONSERVATION

So, how do travelers offset those harmful impacts?

The answer is twofold, according to Andy Ridley, founder of Citizens of the Great Barrier Reef, a social movement that supports positive action worldwide for the reef’s future.

“Every traveler to the reef needs to think about reducing their travel emissions as much as possible, then offset what they can’t, and also look at how they’re contributing to conservation and how they can scale that up,” Ridley says.

“The involvement of tourists in reef conservation is becomingly increasingly important, explains Ridley, with a growing number of tourism operators also contributing to conservation. “Being a tourist on the reef is helping fund those initiatives, so making sure you’re traveling with the right businesses is key,” he says.

Citizens of the Great Barrier Reef also runs the Great Reef Census, an initiative that invites any tourist to take photos of the reef and post them online for other citizen scientists from around the world to analyze and compare to gain a better understanding of how the reef is changing year after year.

“It’s no longer good enough to give your money to one of the big conservation organizations and think they’ll fix everything because we already know they don’t and they can’t,” says Ridley.

“The way conservation is run is up for a massive disruption, and now the question is: How do you mobilize as many citizens as possible to scale up conservation in a way we never have before?”

ANDY RIDLEY

With this question in mind, the Great Reef Census has enlisted about 6,000 people in 50 different countries to help analyze images tourists have taken of the reef.

“By using this cooperative approach, where you’re combining research or science from management authorities, from conservation organizations and from tourism, you’re building a 21st-century conservation operation,” Ridley says.

THE TAKEAWAY

A WIDER LENS

The health of the reef is inextricable from the health of the planet, and it has been said that we now have to save the world in order to save the reef. Ridley sees this message as critical for travelers, who will ideally leave the reef understanding the importance of aiming for a zero-emissions lifestyle back home.

“The reef has become, for very good reason, the poster child for climate change,” he says. “And when people visit, you want them to go away super motivated and inspired, but also understanding what’s at stake. When you see it in all its beauty, why would you not do everything you possibly can to save this extraordinary place?”

And “everything,” explains Ridley, means rethinking how you travel and what you eat and grow, as well as what you buy, reuse and recycle.

A NEED FOR

INDIGENOUS MANAGEMENT

Recognizing the role Indigenous management practices play in protecting the reef is critical.

Juan Walker is from the Kuku Yalanji people in Far North Queensland’s Mossman/Daintree area where he runs Walkabout Cultural Adventures. As a First Nations Australian who has been introducing travelers to Indigenous traditions for the past 20 years, Walker intimately understands the special relationship between the reef, the Aboriginal people who have been custodians of it for thousands of years, and travelers.

“It would be good to have more Indigenous employed as sea rangers, to patrol and look after the Great Barrier Reef, as we have a deep interest in, and connection to, the local environments as traditional custodians,” he says.

“It’s all about sharing knowledge and creating understanding, which opens our minds to seeing how human interaction can be detrimental but, if done the right way, can have a positive advantage.”

JUAN WALKER

Central to this positive impact, says Walker, is moving away from more shortsighted, extractive colonial ways and shifting toward Indigenous ideas of walking lightly on the earth.

“Native people around the world adapted to their environments rather than adapting the environments to suit them,” says Walker. “It’s about finding that happy medium, now, in a modern world.”

THE ‘WELL- INFORMED MESSENGER’

The Great Barrier Reef is a massive ecosystem and the largest living structure on Earth. Such a scope means a closer look at the reef paints a very nuanced picture: For every devastated stretch of reef, there’s one that is pristine and teeming with the kind of life we see in brochures: Orange and white striped clownfish playing hide-and-seek in the fronds of anemones; schools of black manta rays flying elegantly through the water; violet, lime and magenta corals as lumpy as oversized brains — or as delicate as French lace.

Fred Nucifora, director of reef education and engagement for the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, says that traveling with expert guides can help visitors understand what’s healthy and what’s damaged, making sure everyone who leaves the reef does so as a well-informed messenger who can tell the world that while the reef is under threat, it’s not dead, and there are things everyone can do to protect it.

That was the impetus behind the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority creating their Master Reef Guide program, which trains guides to essentially become the best in their field.

“These guides have all the latest and greatest information about the reef, but there’s also a big focus on balanced storytelling,” says Nucifora. “No matter what site a Master Reef Guide takes a guest to, they can point out both the challenges that reef is facing and the amazing resilience it has to face those challenges, and in most cases demonstrate the recovery of that reef because of its resilience.”

The example of the crown-of-thorns starfish is one Nucifora uses to illustrate the importance of balanced messaging and context. At a glance, it might seem like the creature is devastating reefs. But that’s not the full story — in fact, the starfish plays an important role in reef health.

“Their favorite foods are the faster-growing species of coral, so in balanced numbers, crown-of-thorns starfish actually clear out real estate for slower-growing species to grow into, helping contribute to coral diversity,” says Nucifora. “It’s when you get outbreaks of starfish that the balance is upset, and that’s when they can have devastating impacts.”

OPENING MINDS TO REEF REALITIES

Well-informed guides can also help travelers slow down and appreciate the finer details of the reef — the tiny cleaner fish seen grooming the underside of manta rays, for example, or the little-talked-about marine insects and spiders.

“People often come to the reef with a preconceived idea of what’s here based on what they’ve see in coffee-table books with all the colorful corals and manta rays and whales,” says Nucifora. “They’re all here, but a Master Reef Guide enriches the experience by saying ‘Hey, did you see that little goby digging in the sand? Do you know what they’re doing to the reef biologically by doing that?’ It’s those little things.”

Travelers can also help Master Reef Guides monitor reef sites via the Eye on the Reef program, which empowers visitors to collect and share information — including wildlife sightings, pollution, and coral spawning — and benefits travelers as much as it does scientists.

“When you’re monitoring a site, you’re actually stopping and looking and making some judgement-based decisions about what you’re seeing,” says Nucifora.

“By having that deeper experience on the reef, visitors fall in love with it, and because they’ve fallen in love with it, they’re going to go home and want to do their bit to help protect it.”

FRED NUCIFURA